Are doctors and tobacco users unaware of basic facts about harm reduction?

Widespread misperceptions are the norm across the world

[Epistemic status: The claims here are based on my attempt at a thorough reading of peer-reviewed research, but I have no formal medical training beyond college level biology and chemistry. I have a pro-harm reduction bias, both as an advocate in my local community and as a recipient of funding from an aligned organization with past ties to the tobacco industry. For more detail, please see the About page.]

Summary: A wide range of evidence from a years of surveys across the world shows that basic facts about nicotine, tobacco, and smoking, known to subject matter experts for years and sometimes decades, are unknown to a majority of those that make life and death decisions about them. Of particular importance are people who use nicotine or tobacco regularly and the medical professionals that advise them. Efforts to disseminate accurate information could be highly cost-effective interventions to reduce smoking-related disease, but need to be evaluated more rigorously.

Introduction

This post continues the exploration of some of the core claims of tobacco harm reduction (THR) advocates through an effective altruist (EA) lens, with the aim of understanding whether interventions in this area could represent a cost-effective way of improving human well-being. Earlier in this series, I looked at claims about the safety of nicotine and the usefulness of reduced risk products in helping people transition away from smoking. The next important claim is about the lack of awareness of the relative risk of various ways of using nicotine and tobacco.

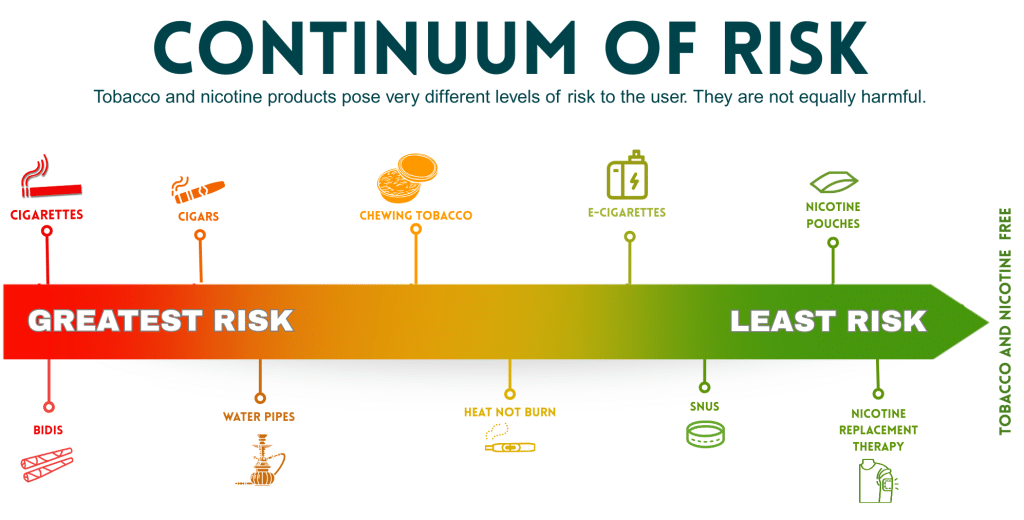

Almost everyone in the field, whether they lean more towards skepticism or enthusiasm for harm reduction, agrees that using different nicotine and tobacco products poses different levels of risk to the user’s health. This fact is often referred to as the “continuum of risk,” with cigarettes generally placed at the most harmful end of the spectrum. And while disagreements abound about the quantification of relative risks for particular methods of ingestion, there is also widespread agreement about the rough order of harmfulness among the most commonly used products.

The distressing claim observed and stressed by THR advocates is that the majority of the general public, as well as that of the most relevant populations — people who use tobacco and nicotine, the doctors that they turn to for advice, and policymakers crafting laws and regulations around their use — are either unable to place the products in even roughly the correct order on the continuum, or are unaware that it even exists and think harms are about the same no matter what they’re consuming. Some of the more strident opponents of promoting THR, on the other hand, have referred to the idea of the continuum as a “hypothesis lacking sufficient empirical evidence” due to its not taking into account second-order population-level effects on smoking initiation.

From the perspective of someone looking for cost-effective interventions to reduce tobacco-related disease, this claim is quite important: even if some products make a significant dent in health risk and are compelling substitutes for the more dangerous ones, if the people using them and the experts those people look to for advice don’t know this, it’s a lot less likely they will try them. If there are large numbers of people unaware of these facts, we have a potentially quite effective way of helping just by informing them, analogously to approaches to sexually transmitted infections and illnesses spread by sharing needles. This post digs into the evidence behind the advocates’ claims, some possible reasons for what they’ve observed, and implications for cost-effective interventions.

Who doesn’t know?

Data around awareness of the science around the harms of nicotine and tobacco use consists mostly of surveys conducted in a number of different populations. This knowledge is obviously critical for people who use nicotine or tobacco since not knowing the effects of switching from one product to another prevents them from being able to make considered decisions. The beliefs of medical professionals are also critical, as these are the people trusted to provide expert advice on health; if they don’t have it, they obviously can’t provide it. The views of the non-smoking public also matter greatly: if people are overall misinformed, even if they never use nicotine, they may support ineffective policies that harm those that do.

A brief sample of the most relevant research can be found below. For even more detail, the Safer Nicotine Wiki assembles an exhaustive range of evidence from surveys of each of these populations across the world.

General public

The average person in most countries is quite confused about a number of different aspects of this topic.

In a 2018 sample taken in the US, only about a quarter of respondents thought vaping was less harmful than smoking

In another US survey from 2020, the number was even lower, with just over a tenth answering “less harmful” when asked to compare vaping and smoking risks

More than a third of people asked in an Australian pharmacy chain thought vaping is as harmful as smoking

A 2016 survey in the UK indicated only about 12% of respondents perceived vaping as “a lot less harmful” than smoking

In 2021, less than a quarter of those polled in Poland believed smokeless tobacco, heated tobacco, or e-cigarettes were less harmful than smoking

80% of respondents to a recent survey in France believed electronic cigarettes cause cancer

The trend in these data also shows that awareness is generally going in the direction of beliefs becoming less accurate over time. For example, in the UK, the percentage of adults who thought vaping was less harmful than smoking dropped from 44% in 2013 to 27% in 2024; in the US, the same numbers went from 41% to 25% between 2013 and 2016.

Nicotine and tobacco users

Similarly to the overall population, surveys show a lack of knowledge among users about relative risk.

A survey of a large (50,000+ person) group of people that smoke across seven different countries found 40-80% of respondents in every country thought nicotine was the primary cause of tobacco-related cancer

Fewer than 20% of adults who smoke in a 2021 US sample believed vaping to be less harmful than smoking

Fewer than a quarter of people who smoke polled in Sweden had accurate risk perceptions about snus

More than two thirds of a sample of people who smoke in France and Germany thought nicotine causes cancer and more than a third believed vaping to be as harmful or more harmful than smoking

Fewer than half of Kuwaitis polled online thought vaping was less harmful than smoking

These numbers have alarmed even advocates and promulgators of strict regulations. The director of the US FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products published a commentary in Nature Medicine in 2023 warning about the health impacts of the lack of awareness of the continuum of risk among people who use tobacco products.

Health care professionals

Given the ample research from the past fifteen years, the extensive training they receive, and the prevalence of tobacco use, one might expect health care professionals to have a solid understanding of the continuum of risk. The largest effort to understand perceptions among this population was conducted in 2022 and consisted of interviews with more than 15,000 physicians in 11 countries on four different continents. Large majorities in each country said that helping their patients to quit smoking was a priority for them, but they displayed many of the same misperceptions as the public and consumers:

More than half of the doctors in each country (including 97% in India) believed nicotine causes cancer

More than two thirds in each country thought nicotine is responsible for COPD

Fewer than a third recommended trying any reduced risk product to their patients for the purpose of reducing or stopping smoking

Smaller studies show results in line with these data. A survey of health care professionals in India indicated more than two thirds believed nicotine to be the main cancer-causing component of tobacco smoke; a survey of US doctors conducted by researchers at Rutgers indicated more than 80% thought nicotine contributes directly to cancer, COPD, and cardiovascular disease; more than a third of UK clinicians surveyed in 2020 either didn’t know whether vaping was less harmful than smoking, or thought it was equally or more harmful.

Why has this happened?

The data are pretty clear that the harm reduction enthusiasts are correct when they claim that massive numbers of people have beliefs widely contradicting the body of scientific evidence. Both common sense and academic research suggest that the lack of awareness of relative risk worsens health outcomes for consumers. Determining the underlying reasons for the confusion is important for figuring out whether it can be cost-effectively rectified. There are a couple of plausible contributing factors.

Rapidly changing evidence base

Some of the most popular noncombustible products are pretty new, and the research on them is recent enough that it hasn’t been disseminated widely enough for awareness to spread. This is most true of heated tobacco, which was launched in 2014 with the introduction of IQOS but only in a few select markets, and to a lesser extent of nicotine pouches and vaping, which began to appear in the mid-2000’s.

This factor is less relevant for snus, which was invented centuries before the modern cigarette and has been studied since the 1970’s, and chewing tobacco, which is even older. While these products have generally become safer over the last few decades, it has been known to experts for much longer that their health risks pale in comparison to those of cigarettes.

Misinformation and fake science from industry

Even when research is disseminated, results indicating a lower risk for anything tobacco-related can be met with strong skepticism due to the long history of reduced risk claims from the industry that turned out to be false. These include the initial long period of the denial of smoking causing cancer, the claims of light cigarettes being a safer alternative, and the idea that filters protect the user’s health by reducing the amount of tar or nicotine ingested when smoking.

It wouldn’t be too surprising for people unfamiliar with and uninterested in the details of research to instinctively dismiss reduced risk claims by pattern-matching to the statements above, which are fairly well-known to be false, especially if they don’t come from sources in which they have strong trust.

Misleading reporting on lung injury outbreak

In 2019, the supply chain of black market THC cartridges in the USA was contaminated with vitamin E acetate, an additive intended to fool buyers into thinking they were buying a purer product. As a result, thousands of people were hospitalized and several dozen died, as inhaling VEA can result in severe, acute damage to the lungs. When the manufacturers realized what happened, they stopped using the additive, and the outbreak ended in early 2020.

Both the extensive media coverage and the poor communication from federal agencies contributed to significant public confusion about the outbreak, primarily by conflating the risks of using illegal THC devices with legal nicotine vapes. This resulted in an abrupt and lasting worsening of risk perceptions both in the US and in other countries.

Misinformation from NGOs

A number of organizations generally trusted by the public on important health-related issues like infectious diseases and air pollution spread false claims related to the continuum of risk in their public communications.

The most prominent of these is the World Health Organization. Its fact sheet on vaping contains a number of false statements and its informational material on smokeless tobacco and nicotine pouches simply lists a number of purported health risks without any mention of their role in harm reduction or their relative risk compared to smoking. A group of UK public health experts called these and other publications out as “blatant misinformation” and a prominent US academic awarded the organization the “Most Egregious Statement About Electronic Cigarettes” for 2024.

Many other NGOs have and continue to spread similar misleading claims, particularly about vaping, including the American Cancer Society, American Heart Association. and the American Lung Association. By lending their brand to these statements, they likely contribute to misperceptions both among the general public and among health care practitioners who are unfamiliar with the evidence.

What has been done?

A number of governments, health departments, and research organizations have recognized the problems detailed above, and have launched initiatives to try to ameliorate them. The main approach has been straightforward: try to disseminate more accurate information to people who smoke and the people they turn to for help if they’re trying to quit.

The UK National Health Service provides what is probably the clearest, most succinct guide on using vaping to cut down on or quit smoking. It provides straightforward answers to the most common questions raised by those interested in using them. The New Zealand Ministry of Health maintains a similar site, Vaping Facts, informing people about product choices, challenges in transitioning from smoking, and supporting friends in the process of switching.

Academic researchers working in tobacco-related fields have also worked on several fronts to correct misperceptions. For example, some university departments have published videos aimed at the public to communicate what they know in an easily digestible way. Others publish podcasts, blogs, and Substack newsletters bringing the latest research to a broader audience. They also push back on incorrect or exaggerated claims in the academic literature through publications in high profile journals like Nature and the British Medical Journal. Medical practitioners with larger public platforms knowledgeable and concerned about the information gap have also contributed to this work, in the form of videos, podcasts, print books, online publications, and articles in popular media.

What could be done?

The numbers show pretty clearly that efforts so far to counter the false beliefs that end up resulting in more disease and early deaths haven’t been adequate. This is where it gets interesting from the perspective of an effective altruist, or anyone interested in impactful interventions for global health. If there are cost-effective ways to bring more accurate information to the relevant groups, these would represent strong candidates for a cause area in global health due to the massive impact of smoking across the world. A couple of unexplored areas stand out.

Gauge effectiveness of awareness campaigns

While some of the efforts to correct misperceptions, like the government websites in the UK and New Zealand, have been quite extensive, there haven’t been any significant efforts to evaluate how many people they reached and how their risk perceptions were affected by them. This would be critical information to inform support of similar initiatives, and EA-aligned orgs like GiveWell have a strong track record in this area.

There has been some research trying to quantify how much people adjust their behavior when learning more about the continuum of risk. These and similar results can serve as a helpful data point when assessing impact this work could have.

Fund organizations disseminating the science

There are a number of existing organizations working on bringing more accurate information to consumers. One might think tobacco companies would have strong incentives to do so and be at the forefront of these efforts, but while this happens to some extent, the inherent conflict of interest resulting from the fact that most of them still rely primarily on selling cigarettes for their revenue, theie continued unethical practices in sponsoring research, and their support of bans on safer products whenever they compete with their own offerings prevent them from being a credible source of advice for the public.

Consumer advocates and informed health care practitioners are likely to be a better fit for providing unbiased explanations of the state of the science. Many of them are highly funding-constrained. For example, CASAA, the largest US-based association representing vapers, will suspend operations in August 2025 because they ran out of funds. The largest international umbrella orgs (INNCO and WVA globally, ETHRA in Europe, and CAPHRA in Asia) all run on small budgets hamstringing their effectiveness, and sometimes faced with the dilemma of either not being able to do much or accepting industry money thereby drawing skepticism from the public and potential donors. The majority of advocacy organizations across the world receive no funding at all and are run on a purely volunteer basis. This represents a big opportunity for impact-focused funders.

Develop more rigorous cost benefit analyses

It’s pretty clear from back of the envelope calculations presented by effective altruist organizations like Open Philanthropy and earlier in this series that increased use of reduced risk products is a net health benefit to the population. A number of open questions remain about whether and how better information could lead to less smoking-related disease:

People don’t switch only for health reasons; factors like product appeal, social environment, and cost are also important influences on decisions

Availability is an issue that won’t be solved through better information alone; for people who smoke in countries where some or all alternatives are banned, knowing what’s safer doesn’t help if you can only get it on the black market (which in turn also makes it less safe)

While the problem is global, the cost-effectiveness of better risk communication may vary among different populations - for example, doctors may find it easier to understand the risk continuum concept and have more opportunity to disseminate it

More in-depth analyses of these and other questions would be critical in helping funders interested in global health determine how it stacks up against other efforts when considering it as an impactful cause area.